How Products Are Made, Part Three — Validation and Production

Ended soon

September 21, 2020 – Copper Magazine, Issue 120 article, written by Robert Heiblim

In Part One and Part Two of this series (Issue 115 and Issue 117), Robert Heiblim took us through the particulars of the initiation and the design processes. We conclude the series with a look at how products ultimately reach the marketplace. We’ve gotten to the point in the product manufacturing process where the team has put together a specific design right down to the actual blueprints and files we can share with our manufacturers. We have budgeted the total expense, come up with projected sales estimatesand have run the financials against our product plan – but now we have to actually make the product.

We’ve gotten to the point in the product manufacturing process where the team has put together a specific design right down to the actual blueprints and files we can share with our manufacturers. We have budgeted the total expense, come up with projected sales estimatesand have run the financials against our product plan – but now we have to actually make the product.

If we have our own in-house manufacturing, we share all this information and get an assessment from them. In the case of third party manufacturers and vendors, which may include subcontractors for specific parts or modules as well as contract manufacturers or even more OEM (original equipment manufacturer) and ODM (original design manufacturer) makers with more extensive capabilities, they will all get RFQ (request for quote) requests, which, after signing some confidentiality documents, serve to get them all the same information in order for them to actually bid on making the product, with all of them on a level playing field.

There is a lot to decide now. Do we build it in-house, or more or less buy it from others? What tools and techniques are needed to build the item? How many will be made, and will be getting the benefit of scaling up production, which will require paying for a large overhead to do so? Do we trust our outside vendors? Will they keep any confidential, proprietary or patented technologies or methods secure until the product is on the market? These questions and more must be answered before making the decisions and proceeding.

And although we think we have a final design, we most likely do not as there will be a lot more feedback on the way now.

Yes, you think you are there or close, but in reality, now that the product has to be built you are going to find out the real cost of building it, and the perhaps unforeseen impact of some of your design choices. There is a giant gulf between making one or more units by hand and actually producing in quantity. It is often in this process that the choices made also have a very big impact on the final price of the product, so for those that care, take note here as our commentary in Part Two about luxury goods versus more mass production items is especially relevant. (With luxury items, there’s more flexibility for prices to go up).

It is often in this process that the choices made also have a very big impact on the final price of the product, so for those that care, take note here as our commentary in Part Two about luxury goods versus more mass production items is especially relevant. (With luxury items, there’s more flexibility for prices to go up).

The selection of the maker is quite important. Usually, they have some specific tools, machinery and skills to fit the requirements you are sending them. However, just like the rest of us they are probably paying the rent on all of this and so their monthly bill will also reflect in what they have to charge. Also, the more sophisticated the tools they own, the more costly they’ll be and the more likely that they will be seeking to keep those tools busy, so volumes of production come into play. Smaller makers may have some or all of the capabilities of larger shops, but like luxury hotels, their rates may reflect the fact that they can’t amortize their costs over a larger volume of units manufactured the way that larger firms can.

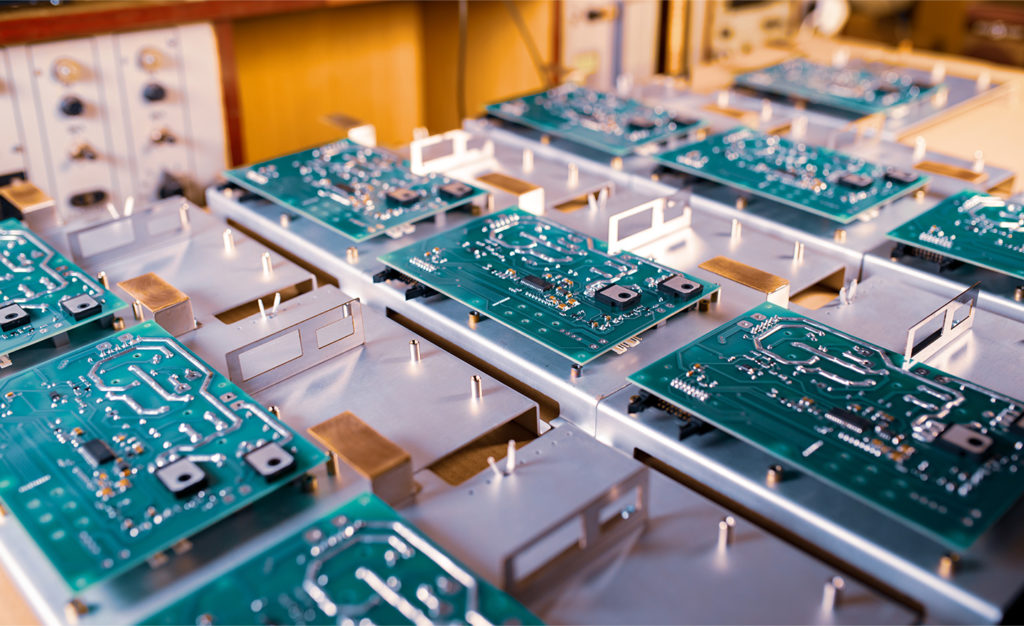

Additionally, the design choices you have made previously now come into play. While works of art, including industrial art, are beautiful, the more unique or non-standard the design, the more it may cost to make it. Uncommon shapes and sizes of anything from cabinets to chassis to PC boards may or may not be compatible with the most efficient and automated tools and machinery. If any hand work is required, this can really run up the bill. I have seen things like PC boards cost five to six times more than usual due to non-standard sizes. These decisions can really push up the cost and resulting selling price.

The factory, whether in-house or outsourced, will look at the designs and validate them. They will examine what the steps of producing and assembling the design will be. The ease or the difficulty of this will determine the time required to make each individual product and the likely yield, which in the end will be major determinants of what the final price of the item will be.

The manufacturer will need to work hand in hand with like metal fabrication houses, cabinet makers, PC board stuffers, transformer makers, chip suppliers and on and on. In addition to their ability to simply make an item, each sub-vendor will have to be evaluated in areas such as their credit worthiness and previous history. For example, do they deliver on time or are they often late?

Along the way, various comments from these vendors on the design choices will arise. Do you insist on using that part or that method of assembly or are you willing to change something to either lower the cost or ease the production? These choices can have a direct effect on the end price of the item to the brand and the final selling price to consumers. Often, the reality is that vendor quotes come back higher than expected and so new choices need to be made to either adjust the price up, or to accept engineering changes in parts, materials or methods to keep the cost in line.

Here a feedback loop often goes back to the initial considerations about the product and the brand. What are you trying to do with this product? Who is it for? How will you market it? The understanding of these things, the biases of the company, the importance of hitting price targets (or not) and other issues will determine the reactions to the feedback, and possibly affect the production timetable and the pricing consumers will see. Looking at a certain type of product – say, a two-way loudspeaker – and considering how many of them are sold should give some insight into the wide range of prices for somewhat similar items and how the amount of them sold can have an effect of their cost.

Looking at a certain type of product – say, a two-way loudspeaker – and considering how many of them are sold should give some insight into the wide range of prices for somewhat similar items and how the amount of them sold can have an effect of their cost.

How one takes this brings up the age-old discussion of value. In my view, value is always in the eye of the beholder and depends on their buying motivations. If you think you are buying art, a limited edition or something lovingly made by hand you may be more than happy to pay a premium for these aspects. Others seeking strictly value per dollar will have a different mindset. In audio, as always, the end results will be measured by the pleasure in the listening experience, and I submit that pleasure is not merely the result of a product’s technical performance but a blending of performance, value, and artistic and design merit. It is very nice to look at those handmade cabinets on Sonus Faber speakers. The unique industrial designs of Devialet, Focal and other brands can be compelling, just as the more straightforward solutions and value of products from Emotiva, ELAC, LSA and others may also be appealing. Vive la difference.

Meanwhile, the validation process will continue at the factory. There are two main streams of validation, engineering and design. Engineering will focus on the stability of the design under various demands. These could include drop tests, exposure to high humidity and temperature, and other evaluations. Conformance to UL, ROHS, CE, FCC and other domestic and international standards will also have to be met.

The design validation process will also determine the manufacturability of the product. Yield, or the number of working versus rejected units is important. Deciding on the quality metrics will affect yield. These can include aspects like how true to color a finish must be, or how many non-working pixels in a screen are allowable, or if any deviations at all are acceptable. Determining what level of product quality is passable and will also help determine the mean time between failures (MBTF). These metrics can also affect the frequency of warranty or repair costs for ongoing support of the product. As you can imagine, the price of the product itself and its positioning are extremely important and the price versus yield can be a delicate balancing act – and one that some firms sometimes don’t properly achieve.

As these processes play out, various samples of the parts and modules that go into the product are also evaluated and tested, with possible changes necessary. You can now see this is a highly dynamic process even though one thought you were done earlier! We proceed from 3Dprinted parts and handmade models to hand-built samples and eventually get to small-quantity pilot production runs of say five to 100 samples, depending on the item. These are usually “tested to destruction” to see what can go wrong and then modified as necessary to improve performance, durability or manufacturability.

We finally get to pre-production runs and the making of things like “golden samples,” which is the factory showing the brand what they think the final version will be. This too is then evaluated, and once approved, full production will occur. At this stage in the game, any changes get quite costly as large purchases of materials will have been made.

These “minimum order quantity” or MOQ amounts vary (whether you’re buying resistors or faceplates, for example) but in general are large bets for the product and the brand, so review and approval of these items at an early stage is serious business and only worth incurring delays or changes if they save the business model by controlling cost, or the market model by ensuring customer satisfaction.

This series has been just a small insight into the overall process of making a successful product, audio or otherwise. As there are many types of products and such a wide scale of possible quantities in which they can be made, it is far from complete, but I hope it helps our readers to better understand why it can take so long and why prices may be so variable. As the entire product creation process from idea to reality can take anywhere from nine months to several years, I also hope I gave some appreciation to the very hard work for any company to produce a product. While large firms have many advantages such as bigger staffs and budgets, it is even more impressive to consider how many fine designs and innovations come from small firms, and the passion they bring to their endeavors. In audio and other areas of consumer electronics, we are all very fortunate to enjoy the fruits of their labors and I have deep respect for all who take on these tasks.

If readers are interested, perhaps in the future we can discuss the hard work involved in actually selling and distributing audio products.

At bluesalve partners, we have an active product development process we can share with clients to accelerate and improve their batting average. Better outcomes are good for everyone, the firms, the industry, and their customers. Let’s all get better together.

Bluesalve partners is committed to accelerating change, growth and success for our clients.